We are stardust…we are golden…

Caught in the devil’s bargain

And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.Joni Mitchell, 1969

The people of the counterculture movement were interested in a new way of doing things. It was a cultural revolution happening on personal and community levels. They were experimenting with what was pleasurable but forbidden or highly regulated, like sex. They were ignoring or challenging the rules and regulations.

Regulation can come from religion or government, through guilt or policy. An example is the regulation of sex. Contraceptive pills were introduced to the public in 1961, but were available only to married women. If premarital sex was a cultural taboo, providing unmarried access to birth control would be down-right hypocrisy.

It took an act of Congress in 1972 to make birth control, “the pill,” available to all women. Free love without easy access to birth control meant the flower children were having babies. A new generation was being born amidst the rebirth of their parents. They would find and create a better way to raise their kids.

Counterculture hippies relied on models of utopia in establishing communes to raise children. Before dropping out of college, they were reading Aldos Huxley who wrote about technology at the cost of humanity, or classics like Henry Thoreau’s Walden, and futurist Buckminster Fuller. They were aware of alternatives. They were dropping and smoking mind-expanding substances.

With families to raise—many had single mothers since everyone had the freedom to split—they left behind the urban political activism that was becoming more radical with groups like the Weather Underground. Hippies approaching the age threshold of thirty collectively re-directing their desire for social transformation toward creating smaller communities based around relationships.

Like the massive college-drop out in the Sixties, there was a second large-scale withdrawal from mainstream society through the mass migration from urban to rural America in the early Seventies. My family was among them.

Generally speaking, those who moved to the country were in one of two camps. Commune people lived together. One person might acquire land, or a group might pool money for a place. They bought old farms and ranches where they built additional small cabins or converted out-buildings into dwellings. The common goal was to grow, make, and share everything. In a later post, I’ll discuss how this turns out.

The other type are back-to-the-landers. Generally, they are organic farming families interested in self-sufficiency and freedom from modern consumerism. They relied on local descendants of homesteading pioneer families to learn how to live off the grid.

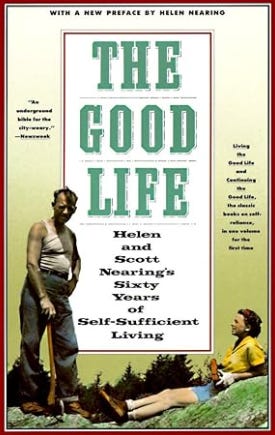

Inspiration based in utopian ideas came from B. F. Skinner, David Suzuki, Buckminster Fuller and others. A popular book mentioned by participants in my study was Helen and Scott Nearing’s The Good Life (1970).

In Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s definition of utopia in Commitment and Community: Communes and Utopias in Sociological Perspective (1972), the word “communes” could replace “utopia,” while the essential word remains vision.

Underlying the vision of utopia is the assumption that harmony, cooperation, and mutuality of interests are natural to human existence, rather than conflict, competition, and exploitation, which arise only in imperfect societies. By providing material and psychological safety and security, the utopian social order eliminates the need for divisive competition or self-serving actions which elevate some people to the disadvantage of others; it ensures instead the flowering of mutual responsibility and trust, to the advantage of all. (Kanter 1972)

Few communes that began since the late Sixties still exist today. Stephen Gaskin’s Farm in Tennessee is still alive, even though he died in 2014 The Farm continues today as an intentional community. But the lifespan of most hippie communes was around two years.

In Comptche, the site for this ethnography, Parker Commune was established in the early 1970s. An inherited ranch, the young Daniel Parker made it easy for people to build tiny cabins and live off the grid, chopping wood and hauling water. For approximately four years they co-operated Parker’s cattle ranch with orchards and organic gardens. People left for myriad reasons and Parker went on to operate the place with his family.

The problems with communal life arose in the very values over which the counterculture generation was grappling: authoritarian structure. Social groups need structure and communes were intentionally anti-structure.

In Hippies and American Values, Timothy Miller found that a recurrent problem on most communes was sexism; while professing liberation and equality, men on communes maintained their mainstream expectations about what women should and should not do on a farm. Women who wanted to drive a tractor where stuck in the kitchen.

Miller’s study defines three reasons hippie communal life failed:

most communes lacked coherent direction and vision,

there was failure to enforce rules because they were against rules,

lack of leadership meant they weren’t able to change communal goals as situations changed.

While Harrington’s The Other America was an early counterculture inspiration, its author later criticized that the movement as reactionary and naïve. He argued that the disenfranchised should not drop out of society, but instead, should continue to work for transformation through political action.

“The poetic demand to do away with machines, so compelling to young people who have never run them or realized their own dependence upon them,” he wrote, would lead to starvation for millions of people if the counterculture were to carry out their utopian agenda.

Although most communes were short-lived, the success is in what was learned from them. The sustainable model of counterculture community turned out to be a community of smallholders, not communes. Utopia remains a dream.

Back-to-the-landers were the other group who set out to live a simple life closer to nature and become self-sufficient. Since many of these neo-homesteaders still remain on their land, they are the most successful and sustainable of the different hippie modalities. Because many back-to-the-lander infused communities thrive today, this branch of the counterculture is the focus of this study.

References for this post:

Harrington, Michael, 1972. The Other America: Poverty in the United States.

Jacob, Jeffrey, 1997. New Pioneers: The Back-to-the-Land Movement and the Search for a Sustainable Future.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss, 1972. Commitment and Community: Communes and Utopias in Sociological Perspective.

Steiger, Kay, 2010. Fifty Years of Birth Control in America.

Turner, Victor 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure.

Westhues, Kenneth, 1972. Hippiedom 1970: Some Tentative Hypotheses.