Following the research shared in previous posts, I’ll continue posting with essays and the occasional audio interview. I want to connect my research about the Counterculture to what we’re experiencing now. I see interesting parallels.

The title above riffs on the book How the Hippies Saved Physics (2011). In relation to our time, How the Hippies Saved Communities could be a new iteration of the book. Not a mere version, but iteration because that means looking for a solution—be it mathematical or social. Iterations are repetitions of procedures based on previous successes, with a common goal. Each iteration is “new and improved”.

We can glean from the hippies, as they openly gleaned from old-timers and non-Western cultures. Our society has gradually adopted practices advocated by hippies in a “new and improved” way. For example: recycling, composting, and organic farming. Current housing alternatives are another example of how the movement impacted how we live. Intentional communities can be seen as an iteration of hippie communes; they solved the problems of unstructured communal life that was too free.

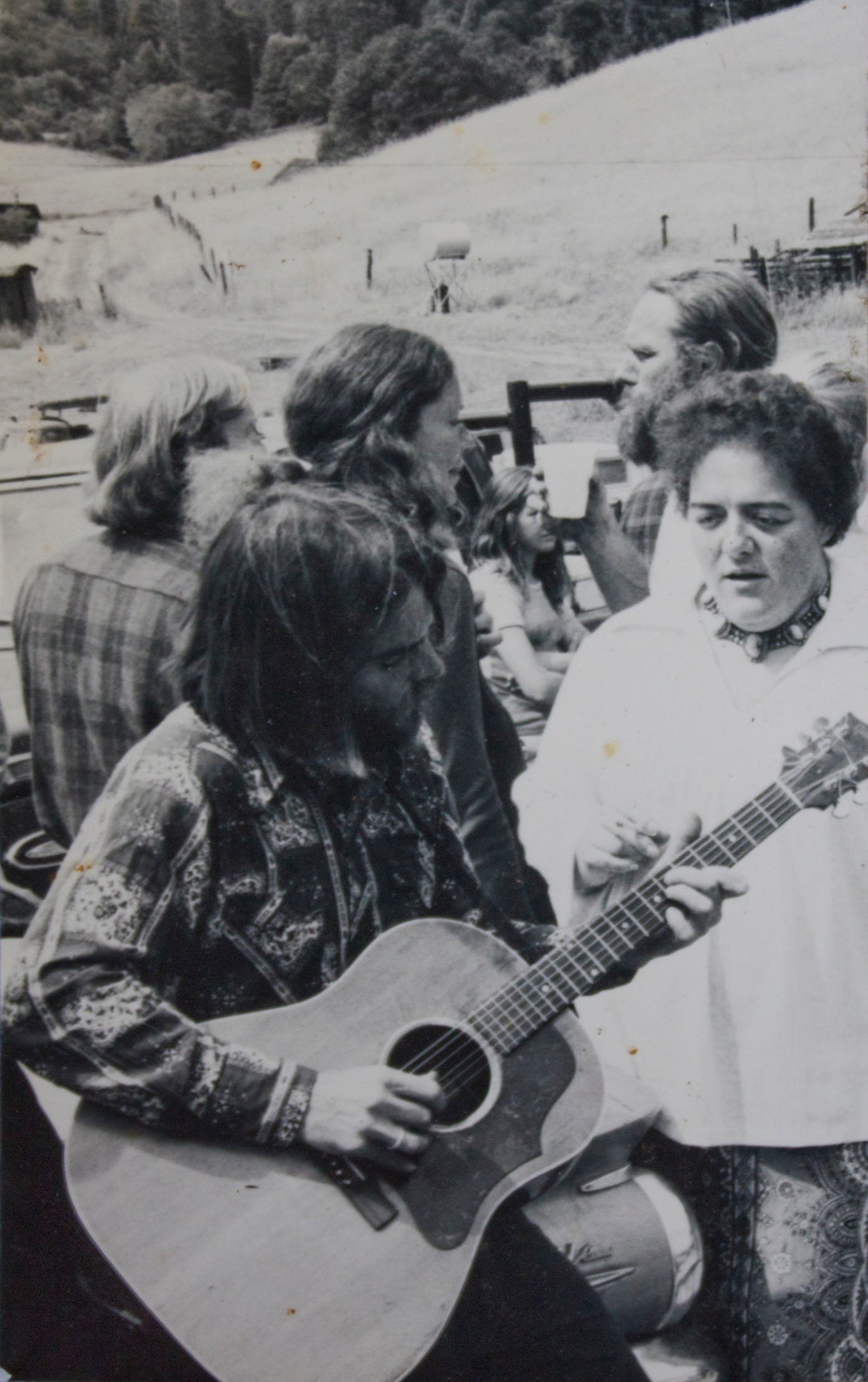

Another iteration of how hippies saved communities includes the rejection of consumerism. Use and waste less, buy and consume less, repair, share, barter, play music, gather locally. Have potlucks. This is communitas.

Communitas, we anthropologists say, is an essential ingredient in community health. Community Health in turn supports individual wellness. The health of a community is related to the health of the surrounding ecosystem—it goes both ways.

There’s a challenge gaining momentum called No Buy Year. Rather than a “movement,” perhaps the term has been stigmatized, a challenge sounds downright acceptable, like Dry January.

There are many upsides to not buying new products and cutting back on what we consume. An obvious example is home cooking with basic ingredients from one’s pantry. Better for our health, cooking in our own kitchens produces less consumer waste, food is more likely to become left-overs than trash, and grocery stores are more affordable than restaurants. If we like the food delivery model, setting up Community Support Agriculture is one way to access fresh, seasonal, food from local growers and producers.

A No Buy Year, an article in The Seattle Times, describes how people are taking on this challenge in local communities. They meet up to share resources of daily life such as clothing, books, tools, and households goods and perishables that would otherwise go to waste. Like swap meets of yore, locals meet regularly to trade stuff and goods. Relationship-building also happens through these exchanges. This is another iteration of counterculture practices.

One No Buy participant said, “The experience is truly life-changing… Not buying makes you realize what you really need, as opposed to things you think you need of just want.” Those taking the challenge shop at thrift stores, buy second-hand, and paying for brand-new things only as needed.

Another person interviewed said, “Embracing a No Buy Year also offers the opportunity to opt out of supporting companies and working conditions that don’t align with my values.”

Boycotts and protests were effective strategies during the Civil Rights era. I remember my mom supporting the table grape boycott organized by Cesar Chavez. Today, the right to protest seems threatened. But we still hold power of our purse. We have choices in what we purchase, to what we subscribe, where we buy, and how our goods are delivered. Because these are daily activities it’s easy to take convenience for granted. We’re encouraged to take advantage of convenience, like it’s a right. A new ad campaign for stuffed charis tells us we have a right to be lazy. Or, the old ad campaign that ingrained in us a right to, “Have it your way!”

Consumer spending accounts for 70% of the American economy at this time. We have a lot of power and should recognize this. When selecting stock or mutual funds for IRAs, many people choose companies and enterprises in alignment with their values. We can do this with our daily spending.

We can host gatherings to share food and talk, share concerns and feelings, discuss ideas. We can play music, dance on the deck or live it up in the living room. For one and all, it feels good. It’s even more important during these times not to isolate, but to be with others.

In the sense that hippies saved communities, a case study is the small town in the redwoods where I did ethnography. The back-to-the-landers repopulated the dwindling town, but showed up in painted school buses and mosaic cars like a colorful theatre troop on a Chautauqua wagon. This caused alarm and apprehension among established residents. Through community events and relationship building, the newcomers helped to bridge the divide they caused by arriving on the scene.

Settled in the redwoods, the community was comprised of loggers and ranchers. Population-wise the town had a surge of newcomers, mostly back-to-the-landers; the population grew from 463 to 549 during the Seventies. Those who stayed shared common ground with the established residents, and the indigenous residents before them: reverence for a place. We Americans move a lot. There is significance in the ability to commit to a place for a lifetime.

The Counterculture was a national movement about creating an alternative to, not a replacement of, mainstream culture. It was about exercising the right to choose, and live according to one’s values. That it has been hyper-criticized is curious.

This social movement wasn’t perfect. It was nascent, as young as the youth who were dreaming it into reality. Today, these same people are our elders.

Resources for this post:

Coven, Bree, 2025. “A No Buy Year.” The Seattle Times, page F8, February 2, 2025.

Kaiser, David, 2011. How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival.

Spicer, Lisa Gruwell, 2012. Finding Common Ground: When the Hippie Counterculture Immigrated to a Rural Redwood Community.