1.0 Collective Effervescence: How hippies changed a rural redwood community

1.0 An back to the land ethnography

About this project:

This story is told as an ethnography, translated as culture writing, in this case counterculture. Looking back to the 1960s and ‘70s, this story and study explore the social-political climate that generated a movement, why it happened, and then visits a small town to see how it all played out.

First published as Finding Common Ground: When the Hippie Counterculture Immigrated to a Rural Redwood Community, it’s titled here as Collective Effervescence. This is a series of articles from my research, fieldwork, and thesis for my masters in Anthropology at Western Washington University.

There are ongoing conversations about this transformative time, what did it all mean?I want to share my research about the counterculture along with a story of community resilience.

The original study can be found at WWU’s Wilson Library in Bellingham, Washington; at the Mendocino Community Library, and the Kelley House Museum both in Mendocino, California. Following this introduction is a series of short articles derived from the seven-chapter publication, posting serially. Thanks for your interest.

Introduction

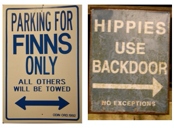

“Hippies took over our swimmin’ holes. There’d be a lot of nudies of both sexes in the river all day down where we used to swim.” Comptche Old-timer.

The remote timber community of Comptche is nestled in the redwood forests along the north coast of California. The town was settled by immigrants from Eastern Europe. I arrived in Comptche as a ten-year-old member of a back-to-the-land family in a purple school bus. My mom bought a small farm, taking part in the city-to-country migration trend of the counterculture.

Listening to how elder Finn experienced the hippies arrival, the sound of his voice was a long-forgotten song. His accent was familiar and nostalgic, and yet I was hearing him differently. A member of an old-time family, he’s the kind of person who gets along with everyone. Listening to him now, I felt a sympathetic resonance, something I never considered: What did it feel like when the hippies moved to town?

Returning in 2011 to conduct ethnographic research in Comptche (pronounced “comp-she”) gave me a chance to understand and articulate what I could not in my youth. I was motivated by the sense that something unique happened here during the Seventies. A wave of back-to-the-landers migrated to this rural redwood community first created a period of conflict with long-term residents, and then affected positive social change.

Something noteworthy happened here. That’s why research participants chose to contribute their thoughts, experiences, reflections to this study. We all wanted to understand what happened, how it worked.

The variety of views among participants regarding what brought peace to a town in conflict ranged from children to time. One respondent came close, surmising peace came to Comptche through “potlucks.”

What I found: community events provide common ground and a way for newcomers to integrate into the Comptche community.

Community Events and Common Ground

Social science ancestors Emile Durkheim (1858-1971) and Victor Turner (1920-1983) established that social gatherings and rituals are vital elements in healthy communities.

Durkheim explains that collective effervescence, or exuberant social events, support social cohesion that contributes to a healthy community. Events in Comptche attract people to common ground who otherwise live in remote settings. Social gatherings are a key element in understanding what works well in Comptche because they create a synergy between people and place. These synergistic gatherings in turn support a virtual civil commons and a unity of purpose. The result is rural resilience.

This ethnography shows how the people of Comptche were able to overcome values conflicts between newcomers and old-timers through a tradition of social gatherings. People could suspend their differences and gather on common ground. These virtues were hard won in Comptche.

The town’s social structure “didn’t have room,” as one old-timer stated, for counterculture newcomers. Comptche’s eventual acceptance of immigrants occurred through a deliberate process. Community gatherings have become a mechanism providing numerous beneficial outcomes for people and place.

This ethnography demonstrates that it’s not just “getting together,” but gathering around common values that promotes and nurtures the functions of a healthy community. Well into the new millennium, Comptche has a social structure that honors traditions and integrates newcomers.

In the spirit of contemplating something on a small-scale in order to understand things on a grand-scale, what happened in Comptche during the 1970s is a study in overcoming community conflict. Finding common ground is a crucial first step, and then effectively maintained through community traditions and opportunities to gather.

Nice start, Lisa!