The Counterculture had no elders. A central driver of the youth movement was disassociation from middle-class parents, values, ideals, and beliefs. They were changing values, discussing new ideals, and learning about different beliefs.

But the adage, “Never trust anyone over thirty,” had to die once the hippies crossed that threshold in the 1970s.

Undoubtedly, there were participants over thirty but most were young, notably the singers, musicians, writers, and artists who were communicating the messages and meaning of the movement.

“If the ideals of the Sixties had prevailed it would be a world, where people lived gently on the planet without the sense that they have to exploit nature or make war upon nature in order to find basic security. It would be a simpler way of life, less urban, less consumption-oriented, and much more concerned about spiritual values, about companionship, friendship, community.” Theodore Roszak

The work of two elder scholars helped me interpret my findings in this study, and also understand the era I lived through. The scholars are UC Berkeley history professor and author Theodore Roszak (1933 - 2011), and Robert Theobald (1929 - 1999), a futurist and economist.

I had the honor of working with Theobald in 1998, editing his recordings for an audio series, The Healing Century: A message of hope for the new millennium. He used phrases like: “Life as a journey. Staying healthy. Work as right livelihood. Enjoying the rapids of change.” His work sheds light on what makes communities resilient and sustainable. When I visited Comptche in 2008 for a Mendocino High class reunion, I found the kind of resilient community described by Theobald.

Theodore Roszak was in his thirties during the Sixties, a beginning professor at U.C. Berkeley. He wrote that he was, “fascinated with the political ebullience of college-aged, and even high-school aged, youth as the rest of the world around me.” Observing and listening to his students, Roszak wrote a book, published in 1969, that defined the movement: The Making of a Counterculture.

About the book, The San Francisco Guardian stated:

“The term counterculture, which became a near-universal shorthand for the world of the rebellious young, identified a shift away from social activism towards what Roszak called the politics of consciousness.”

At the end of his life, Roszak published a message to Counterculture participants in his last book: The Making of an Elder Culture: Reflections on the Future of America’s Most Audacious Generation.

In his book, he explores the values, ideals, and changes that counterculture boomers bring to the social realm. He calls upon this population to pick up the unfinished work of their political activist and hippie youth, such as environmental activism, human rights, organic food, peace. It’s an exercise in practical nostalgia because:

“It mines the past to find solutions for the future. In that respect, it stands somewhere between a critique and an appeal.”

Through experience, Counterculture youth found the root meaning of utopia and discovered imperfection. Seeking anti-structure, they created a new structure. Roszak encourages revisiting the ideas of communalism and utopian theory to discover what worked:

“The original goal of utopia was to create a community where personal autonomy, commonplace decency, and self-respect could be achieved.

And what did that require? Sharing the wealth in ways that offered basic security and equal access to the good things of life.”

Revolutionary movements get hung up on the actual revolution and neglect the continuity that remains available among participants. What works is to channel the momentum into community-building. Roszak points out that the Counterculture was the first such movement to advance beyond the excitement of the revolution.

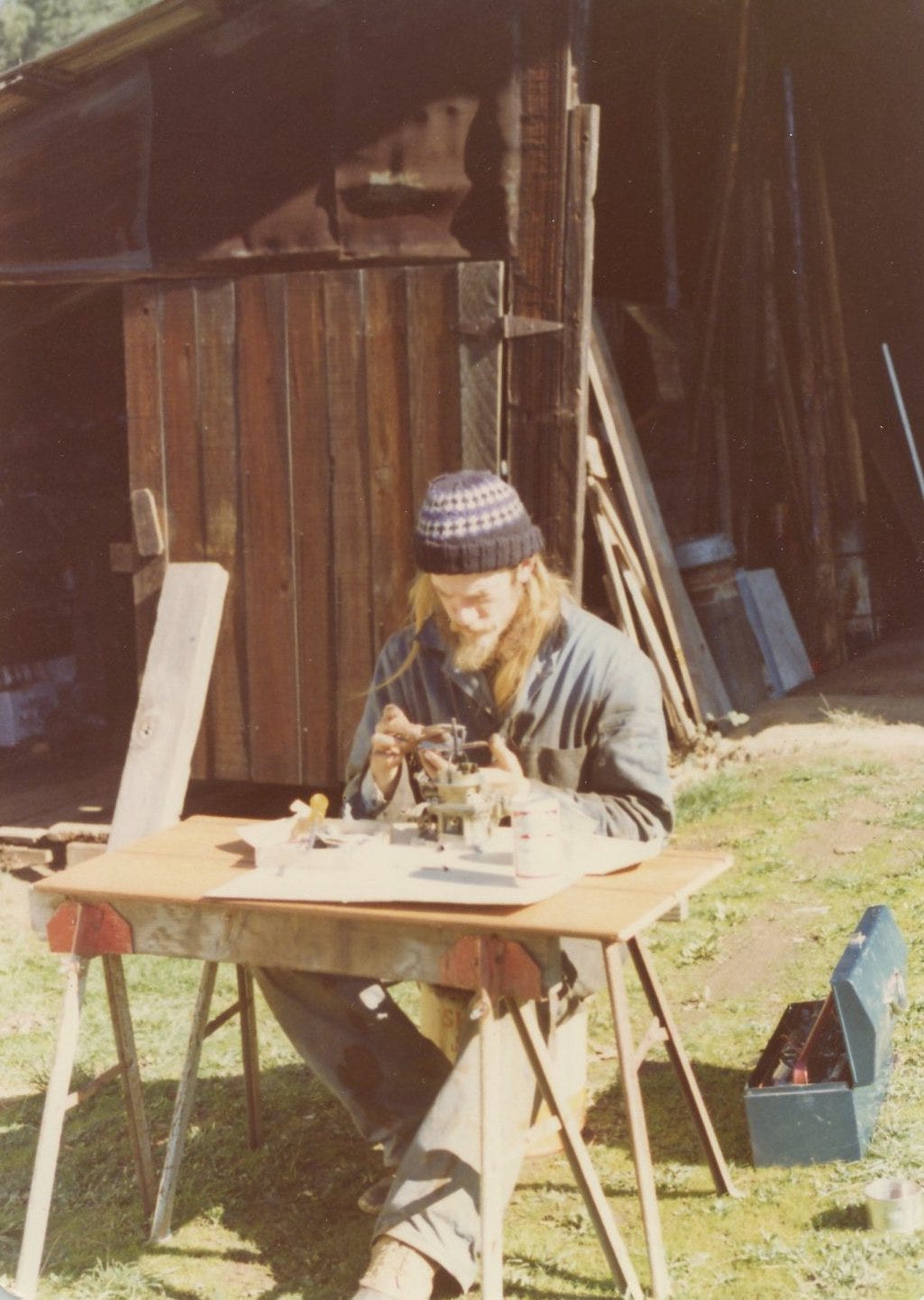

1970s Comptche is a case study of this phenomenon, growing from movement ideals to sustainable community. The back-to-the-landers planted seeds in fertile ground for a contemporary harvest of experience and ideas that relate to the larger divide in our country today.

In a PBS interview Roszak, who lived in Berkeley, described the movement as if he lived in Comptche:

“Community was one of the great words of this period, getting together with other people, solving problems, enjoying one another's company, sharing ideas, values, insights. And if that's not what life is all about, if that's not what the wealth is for, then we are definitely on the wrong path.”

The Counterculture now has elders. They have valuable insight, more so during these times, starting with: How do we all get along?

This entire research project was sparked by that question: How did the people of Comptche make peace from chaos? The answer, which can be read as both cheeky and serious: boogie with the locals.

Next up: Comptche and the Civil Commons

Resources for this post:

Gladysz, Thomas, 2011. Obituary: Theodore Roszak (1933-2011). Electronic document. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jul/27/theodore-roszak-obituary

Roszak, Theodore, 1969. The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition.

Roszak, Theodore, 2009. The Making of an Elder Culture: Reflections on the Future of America’s Most Audacious Generation.

Spicer, Lisa Gruwell, 2012, c 2024 . Finding Common Ground: When the hippie counterculture immigrated to a rural redwood community.

Theobald, Robert, 1997. Reworking Success: New communities at the new millennium.

Theobald, Robert, 1998. The Healing Century: A message of hope for the new millennium. Australian Broadcasting Corp.