Finding #1 of 6: Many voices tell the story, each like a piece in a quilt.

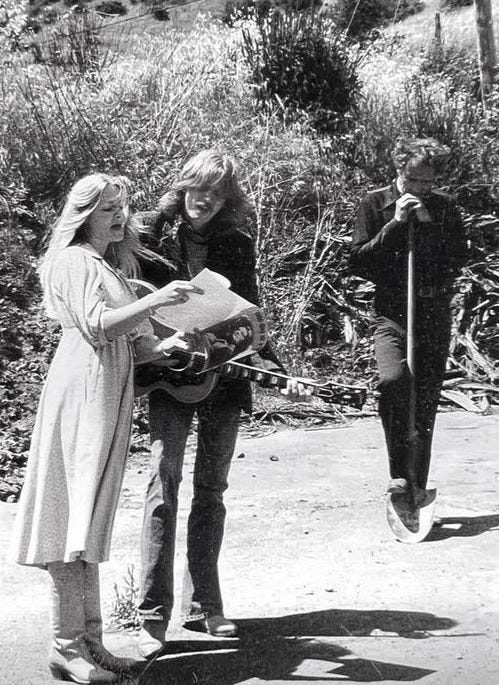

The process of collecting, recording, analyzing, and arranging Comptche stories from the 1970s revealed a collective narrative. The narrative provides a way to understand a common history from different angles.

Participants in this project contributed their stories to social science scholarship by sharing lived experiences. When a person shares a story it becomes an opportunity for both reclaiming one’s self and defining their role in a shared history. Whether sharing through research or personal reflection as we tell and retell our stories, we are shaping our sense of self and community.

This ethnography of Comptche during the Seventies is also auto-ethnography because I included myself in the study. Designing the research this way enabled me to explore my personal experience from this time and connect findings to a wider cultural meaning.

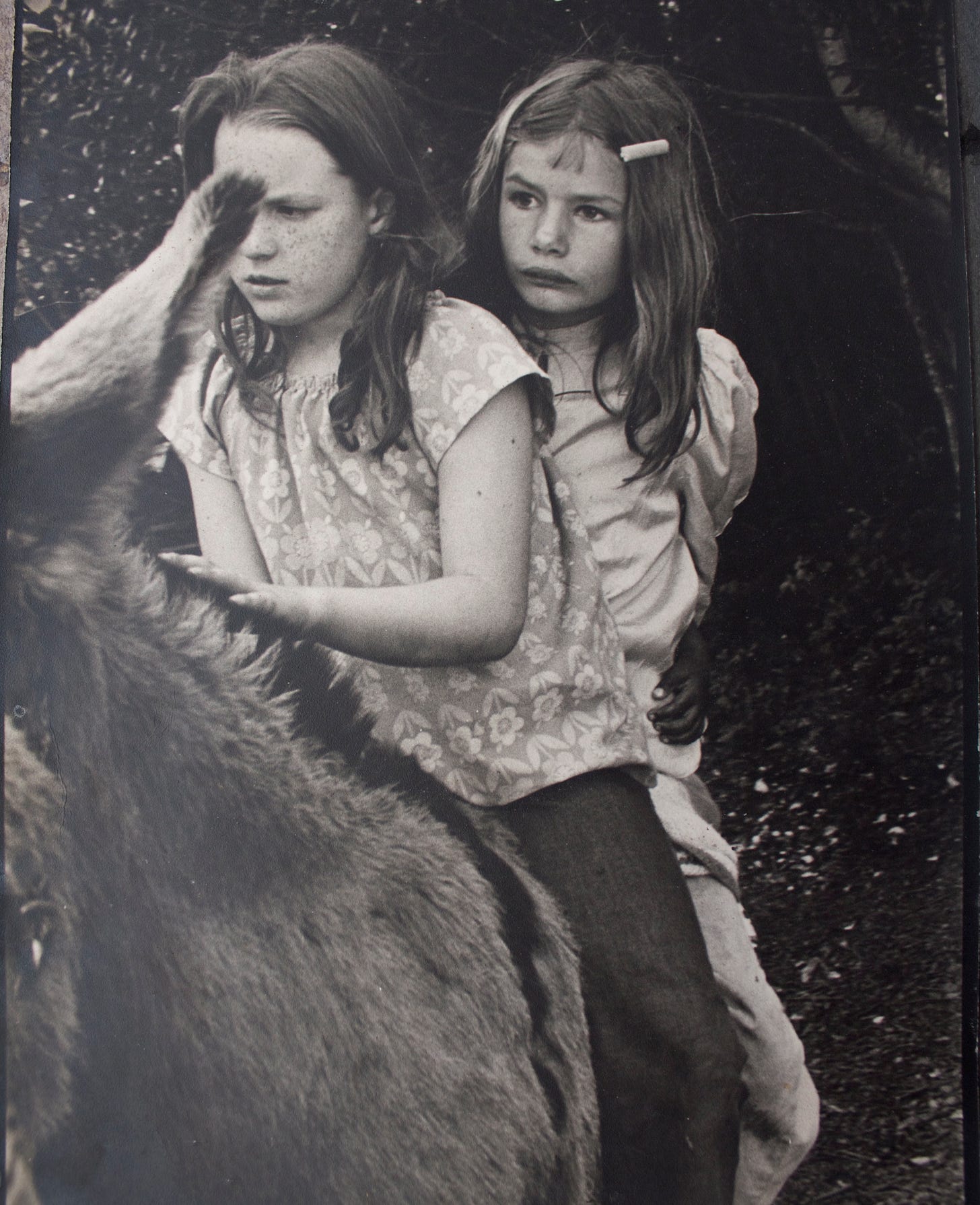

Always on my mind was the question: how does my lived experience compare with and reflect the lived experience of other back-to-the-landers—especially those who, like me, were children?

Now, “the Seventies” is not just a phase we endured or a time mythologized and cast with stereotypes. Together, we told a story that provides transformational meaning. The meaning provides an example of what works and can be applied elsewhere.

Each participant contributed a story piece. In making sense of the data I had collected, it became clear that each voice was telling part of a bigger story. This follows their tradition of community quilt-making. The stories are not all the same but they work together. Piece-by-piece, a pattern emerged like a story mosaic.

By gathering and reconsidering our story pieces, I unintentionally created a way for participants to understand the Other as much as ourselves. According to participants, much of this new understanding occurred following the community presentations of my findings.

Stories of people who have had the same experiences create a emotional binding in the collective story. Sharing stories provides a function comparable to old-time cabins with removable walls for dancing: story telling brings us together, draws us out of isolation.

“[Storytelling] provides a sociological community, the linking of separate individuals into a shared consciousness. Once linked, the possibility for social action on behalf of the collective is present, and, therewith, the possibility of social transformation.” Laurel Richardson, 1990

We build community on foundations laid by our ancestors. Someday, we will be the ancestors, remembered through the stories we leave behind. It’s meaningful to acknowledge our singular stories in the historical arc and record of a place.

Archival photographs of giant redwoods make us grateful for the remaining behemoths at Montgomery Grove State Reserve. The same photos are also painful reminders of what we have lost. Stories tell us who and what was once here.

On the threshold of a new historical cycle, it’s on us to preserve knowledge of the past, especially examples of resilient communities. The Comptche community is well-served by remembering shared stories: the work of the Comptche Area Citizens Advisory Committee, or how the town without a church overcame differences and built a chapel.

How will future generations know our story, unless we do the work to record, photograph, paint, draw, print, publish, and contribute to the record? New chapters are being lived to be told in decades to come as contemporary local knowledge refreshes the next generation of research and storytelling.

Up Next: 7.3 Feeling Bad About Feeling Groovy

Resources for this post:

Etherington, Kim. 2004. Becoming a Reflexive Researcher: Using Our Selves in Research.

Richardson, Laurel. 1990. Writing Strategies: Reaching Diverse Audiences.

Spicer, Lisa Gruwell. 2012, C 2024. Finding Common Ground: When the Hippie Counterculture Immigrated to a Rural Redwood Community.