"Don't churn cold milk for butter." Old-timer

“What was most important was no one had all the knowledge or resources and we were forced to share, trade, and help each other. There was a norm of sharing, rather than hoarding.” Newcomer

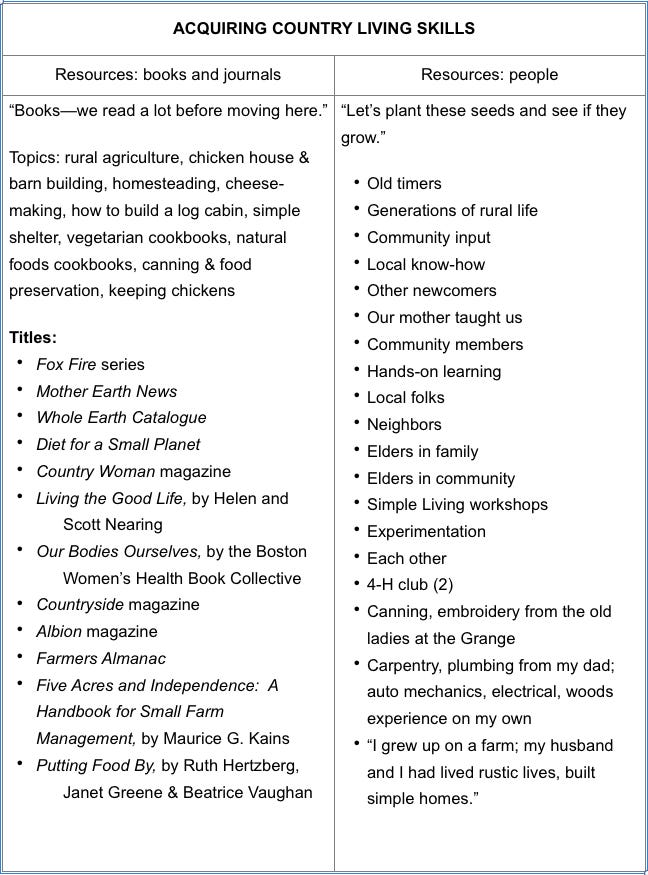

Comptche’s new immigrants used a variety of means to learn how to live on the land. Many back-to-the-land hippies were college educated so knowing how to do research helped them to acquire some of the knowledge and skills needed for successful rural living, but the immigrants also knew that the established residents were a valuable resource.

The problem was that many of the old-timers found the hippies offensive and wouldn’t associate with them. Some back-to-the-landers wanted to figure things out for themselves and didn’t want old-timer advice.

Respondents who were kids children during the 1970s wrote:

“We learned from scratch,”A lot of hippies were so ornery we re-invented the wheel. Myself, I learned by watching the failures of my parents, I’ve been watching people build incorrectly for thirty years.”

“Mom wanted to move us to the country to teach us how to live off the land. She taught us how to can, we made all our food from scratch, we picked berries, had chickens, pigs and two cows. We made butter and ice cream and traded milk for firewood.”

For respondents who were among the established old-timer residents, country savvy was a way of life. The early pioneers of Comptche passed down their knowledge to descendants remaining on family land through many generations.

"My family were old time Finns and we always knew how to live there. All the information we have came before my time when my grandparents first got the property. We just do what needs doing.”

“My father was born and raised in Comptche so he taught us everything we needed to know. If you didn’t know something, you asked your neighbor for help.”

Staying overnight with girlfriends who had old-timer families was a way I learned about rural life. In warm weather, we slept outside in sleeping bags and named constellations and counted falling stars. On one such sleepover at the home of an old-timer family, I woke in the morning to the sound of grass being pulled up from the roots. I looked over and saw my friend’s sleeping bag was empty. Following the sound, I observed her sitting across the yard with a headless chicken, plucking the feathers.

Country living is learned by observing and listening, by doing, being inventive. Old-timer children had chores they worked into their school day, such as chopping kindling, feeding the animals, collecting eggs, milking cows.

“We just grew up that way. Mom was a widow with two kids. She was born and raised here, so she already knew how to live in a rural place. Mom would laugh about the newcomers using wood cookstoves. ‘Why would anyone want to go back to that?’”

Newcomers listed things they needed to learn as a homesteader: building, plumbing, developing land with roads, parenting, fixing things with salvaged parts, canning, living without electricity. “Money was scarce for everyone. We were all too poor to buy what we needed, we had to either make it or make do without it.”

One newcomer respondent wrote that before moving to Comptche, she was a vegetarian. She and her husband decided, like many people in Comptche, if they were going to eat meat, they would raise it themselves. Butchering meat and canning fish, however, turned out to be more than some of the newcomers bargained for:

“I learned to can salmon cheeks with Joel B. for winter protein. We went to the Noyo Harbor processing warehouse, and came home with pounds of fish to can on a wood-burning stove. I learned I didn’t want to do it again.”

But the meager incomes of the back-to-the-landers also made them resourceful. Being creative with the materials on hand brought discoveries and rewards:

"I made a zucchini pineapple jam—I entered it in Mixed Jam category at the county fair and won 1st Place.”

Learning to live in the wilds of Comptche was dependent upon building and maintaining relationships among all people in the community. Immigrants needed to learn the tacit rules specific to that place, as well as the practical skills of daily life.

It took the first few years of the 1970s for some of the old-time population to get past the divisive elements and accept the newcomers. Most old-timers eventually opened up and shared their country living skills, knowledge, and friendship. Personal relationships became the key that opened the process of transformation from a conflicted to a resilient community.

This table shows how Comptche residents learned to live off the land.

Reflecting on this post today and how I grew up with people so openly in love with Earth, the only home we have, who dedicated themselves to raising healthy kids in diverse communities on a healthy planet, who read and heeded the call made by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962—I hope it becomes clear that since the 1960s, and the Counterculture movement, there have been people—back-to-the-landers in particular, who have been working to avoid the very ecological-social crises we face today. What good did we do? Hippies were shamed and ridiculed as tree huggers; in the 1980s, Newt Gingrich said, “Hippies are a national embarrassment.” Now we have systems collapse. Do you know how to garden?

Next up: Volunteering, Part of Life in Comptche

Resources for this post:

Spicer, Lisa Gruwell, 2012, c 2024. Finding Common Ground: When the Hippie Counterculture Immigrated to a Rural Redwood Community. Western Washington University Press.