“The hippies proclaimed a disavowal of consumer culture… the counterculture sought new values for living, values that will fill the spiritual emptiness created by material affluence.”

Timothy Miller, 1991

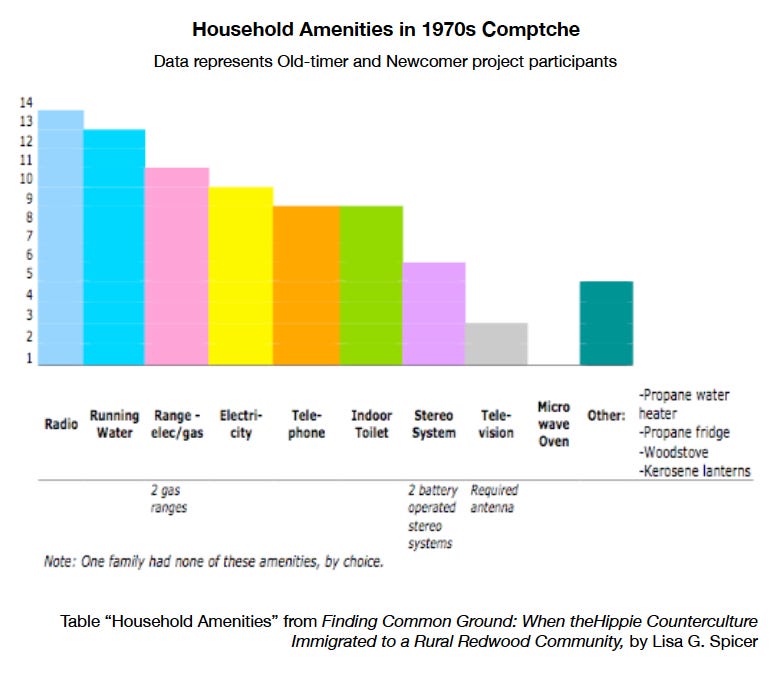

In 1970s Comptche, the community as a whole held a similar ethic toward income and expenses, regardless if one was an old timer or a newcomer. This is reflected in the table below, Household Amenities in 1970s Comptche, based on participants’ responses.

A radio or audio cassette tape deck were the only sign of mainstream modernity for some back-to-the-landers, and only then because of batteries. Music was an important part of the scene, and back-to-the-land households with electricity usually had stereo systems. A few old-timer families had television, if they were able to rig an antenna high enough in a redwood tree.

I estimate around half of the back-to-lander community lived without electricity by choice. Propane-powered appliances such as refrigerators and water heaters were found in both old-timer and newcomer homes.

The old-timer participants reported that by the 1970s, their homes had access to electricity, running water, indoor plumbing, and modern kitchen appliances, including washing machines and dryers, but drying laundry “en plein air” remained common.

Old timers were aware of how the back-to-the-landers were living and found it odd because their families had worked hard get PG&E to bring power lines inland.

An old-timer respondent said, “The hippies were living off the grid, and here we just got on it.”

Another wrote, “The back-to-the-land thing was interesting. But we were wondering, outhouses? Why?”

An old-timer participant wrote about the Parker Ranch, for a time known as The Parker Commune, neighboring her family’s ranch. “It was the only so-called hippie commune in Comptche.”

A childhood friend of mine lived on the Parker Commune in a small cabin with her mother and little sister. Their kitchen was made from camping equipment. They hauled water and heated the place with a small wood stove, read by kerosene lamplight, and slept in the loft. The old ranch house was communal space. In the dining room sat an old player piano. We kids learned how to change the scrolls and delighted in listening to popular song from the early 1900s, the keys being pressed as if a ghost was playing the piano.

Relationships were forged among Comptche residents who, historically, have depended upon one another for survival. This includes participation in the local micro-economy.

Newcomers say they shared resources with each other, such as chainsaws and other tools, because they couldn’t afford to own every tool they needed. Borrowing and returning tools was a component of social life, and visiting over coffee was often part of the exchange.

Newcomers hired and bartered with old-timers for work requiring heavy equipment commonly used on ranches, such as tractors and rototillers. One old-timer was a land surveyor. Another was a dowser who helped newcomers locate water for wells, and yet another old-timer with a back-hoe helped the immigrants dig those wells.

Back-to-the-landers knew their survival depended upon good relationships with all local residents and seemed to be patient in allowing those relationships to form. Over time, the established residents grew to appreciate the immigrants and the talents and abilities they brought to the community.

There are accounts of hippie kids growing up in Comptche who befriended old-timers and in doing so, built bridges.

“It took me thirty years, but now I’m friends with the locals. I value them for what they know,” said a newcomer respondent who was a young child in the Seventies. An elder old-timer had become a recluse in his isolated home in the woods. He refused to see even his family, who resorted to leaving his dinner on the porch. The back-to-the-lander, who was then a young man, routinely snuck across part of the old man’s land to tend pot plants, almost daring him to come out.

“I was sneaking by his apple trees and he yelled, ‘Hey! I see you!’ So I walked over and we talked. I turned him on, smoked a joint, and he told me I didn’t have to sneak across his place anymore. The old coot came out of his house, started talking to people again, and became the town nuisance for the last five years of his life!”

Next up: Living in Comptche is Hard Work

Resources for this post:

Miller, Timothy, 1991. The Hippies and American Values. University of Tennessee Press.

Spicer, Lisa Gruwell, 2012. Finding Common Ground: When the Hippie Counterculture Immigrated to a Rural Redwood Community. Western Washington University Press.