Like world-building in a novel, the first nine posts in this series describe a point in time in America, which is the setting for this study. We now have a common overview of the two-decades long movement and why it was happening. We see how mainstream society responded.

The term “hippie” originated among California journalists and the label stuck. In the early ‘60s Herb Caen, a popular columnist with the San Francisco Chronicle, derived the term from beatnik. San Francisco Examiner reporter Michael Fallon wrote a series in 1965 about how the hippie population influx helped revitalize a neighborhood in decline where the rent was cheap:

“Haight-Ashbury is the City’s new bohemian quarter for serious writers, painters and musicians, civil rights workers, crusaders for all kinds of causes, homosexuals, lesbians, marijuana users, young working couples of artistic bent and the outer fringe of the bohemian fringe—the ‘hippies,’ the ‘heads,’ the beatniks.”

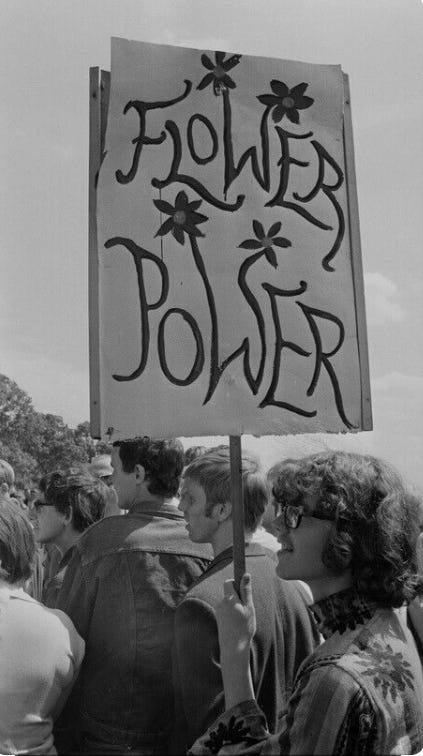

Participants in the movement called one another heads, brother, sister, one of us.

At the time of my research, 2010-2013, there weren’t many studies about the counterculture. I suspect because hippies still wear the badge of national embarrassment. Even my graduate committee snickered and made puns, but when I defended (presented) my thesis, the room was packed with professors and students alike.

I found a few studies that were helpful to me personally as much as my research about the counterculture. For example, there are three basic types of hippies:

Urban/college activists

Commune dwellers

Back-to-the-landers

This is when I discovered something about who I am and where I came from. We were back-to-the-landers. I didn’t know that’s who we were. What I did know, we were the ones going to the country.

Listen to Canned Heat’s Goin Up the Country, with Jim Horn’s magical flute opening and you’ll get a sense of that feeling of collective flight. Here’s a few lines:

“I’m going up the country, Baby, don’t you wanna go?

…I’m going to leave the city, got to get away.”

When I returned for my high school reunion in 2008, I was amazed by my former hometown. There was no conflict. The old timers were as happy to see me—a former Comptche kid all grown up—as were the back-to-the-landers in their vastly improved homesteads. This is when and where I heard myself asking the question that would become my thesis in Anthropology. How did they go from divided and obnoxious to a peaceful community where everyone gets along?

In 2009, I conducted a year of field work, when I interviewed participants, visited sites, dug through county records and newspaper archives, and had conversations with people. All of the participants lived in Comptche (“comp-she”) during the Seventies and some of them still live there today, maintaining homesteads established first by Finnish immigrants and later by back-to-the-lander families.

The peace that exists there today can be pinpointed to an incident in 1975 that brought the old timers and newcomers to the same table. Mendocino County mandated all towns to submit a general plan. Many of region’s towns were unincorporated at that time and some remain so, intentionally.

Doing research in Ukiah at the County offices, I learned that Comptche was the only town to handle the task democratically. The old-timers and the newcomers appointed representatives from both “sides.” Over the next three years, they met monthly at the Grange Hall, where hippies had been blackballed when attempting to join in the early Seventies.

To this on-going conversation, awkward at first, the old timers brought generational knowledge of the land and the newcomers brought education and new perspectives. They were able to find common ground based on why they chose to live there. They confronted their fears about each other and found they had common values. With shared values, they were able to establish a vision for the community’s future.

For any community common ground is the civil commons, the shared foundation of water, roads, schools, post offices, parks, fire departments. For rural communities, this shared space includes things like nature, farmers markets, community halls, and barn raisings—which are a model of reciprocity. These are tangible things that are valued in common by everyone in a community.

In the next sections, we will hear about what life in Comptche was like for newcomers and old-timers during the 1970s.

References for this post:

Comptche Advisory Committee, Comptche Conservation Plan, 1978. Ukiah, CA: Mendocino County Planning Division

Fallon, Michael, A New Paradise for Beatniks, San Francisco Examiner, Sep 5, 1965.

Sumner 2005

Wilson, Alan, songwriter, Going Up the Country, 1968. Producer Canned Heat, Skip Taylor.