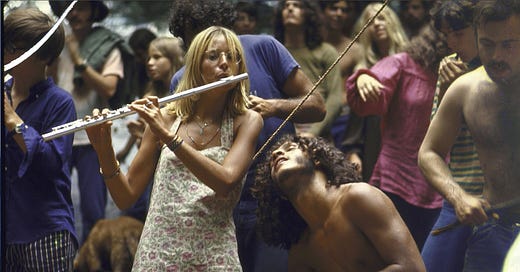

Communitas happened at love-ins and it happens today at concerts, dances, community events, places of worship, parades, festivals. It’s shared joy and good feelings, a quality that transcends social structure. In this way, communitas is an important part of the health of any community.

Communitas involves a ritual process of preparation. This could be event planning, publicizing, having tickets or some kind of exchange for entry. Along with preparation, there is structure, such as a physical place and a theme or organizing reason to have the gathering. Afterward, it will be said, a good time was had by all.

These events produce a kind of group high called collective effervescence—the point in time where everyone is in the groove dancing, singing, praying, cheering. It takes time and interaction to reach this point. As a phase of communitas, collective effervescence is the group climax.

In The Ritual Process (1969), anthropologist Victor Turner finds the values of communitas are apparent in the collective culture of the Beat generation and their cultural heirs, the Hippies. The values are expressed through peace symbols, flowers, long hair, long dresses, colorful comfortable clothing and state of mind.

The hippies’ adoption of poverty, the topic of last week’s post, was about the rejection of consumerism and capitalism. Turner studied the hippies and the Beat generation, preceding them, and finds they both adopted the stigma of poverty.

“…dressing like ‘bums, itinerant in their habits, folk in their musical tastes, and menial in the casual employment they undertake. They stress personal relationships rather than social obligations, and regard sexuality as a polymorphic instrument of immediate communitas rather than as the basis for enduring structured social tie.” (Turner, 1969)

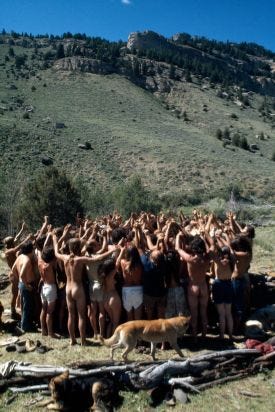

He implies that hippie events such love-ins or tuning on through acid trips, enabled them to “get on the bus” to communitas for the sake of the group high part, without all the ritual preparations and the structure that precedes and supports such human experiences. The instant high is not sustainable. This is an important understanding for this study. Consistently, when hippies rejected structure, from relationships to housing, things fell apart.

Learning from pre-industrial peoples, Turner established that communitas is a dimension of all societies past and present, and its parallel dimension is structure. One of his examples is a rite of passage ritual where, “men are released from structure into communitas only to return to structure revitalized by their experience of communitas. What is certain is that no society can function without this dialectic.”

Communitas is an important state of being with fellow humans that transcends structure. Hippies desired communitas because it provided existential meaning about being together. The experiment in togetherness without all the trappings was unsustainable, as the commune movement shows (discussed in an earlier post).

In Kelly Luker’s article Commune Sense, about hippie kids who grew up on communes, Zane Kesey—son of Ken Kesey of the Merry Pranksters—summed up the failure of this type of living arrangement. “My dad said that the commune idea of sharing was great, but it all breaks down in the fridge."

Having no role models, hippies had to discover for themselves the importance of structure to hold all that freedom. Communitas cannot be sustained if the structural and organizational needs of human beings are not addressed. This is one reason why most of the hippie communes did not last.

My study shows that where the counterculture movement thrived is in the context of back-to-the-landers, who found how to balance communitas and structure. Many of these people are still homesteading today. You will meet some of them in the posts ahead.

References for this post:

Luker, Kelly 1996

Turner, Victor 1969

Up Next: The Hippie Hangup: Critique, Fear, Myth